The Federal Reserve’s stated goal of moderating the business and credit cycle while maintaining full employment through enlightened policymaking demands a macroeconomic understanding of such a comprehensive and elegant nature as to rank alongside a quantum theory of gravity. It also offers a hypothesis to explain the surprisingly resilient decoupling of risk assets from fundamental reality.

While I hate to add to the heap of market-as-degenerate gutter drunkard analogies tossed around by the media and punditry (especially in my first post), here’s one more for you:

The old notion that the Fed’s job is to ‘take away the punch bowl’ before the party got out of hand seems a bit outdated given the unprecedented scale of government involvement in capital markets. The events of the past year have generated a policy response more akin to throwing a carte blanche booze and drug bonanza with the hopes that you’ll be able to gradually cut off the raging crowd before anyone gets out of control and your place is burned to the ground. Think something between a Big-10 game day kegger and the party Jonny Depp throws in Blow.

Last week’s FOMC statement added a series of qualifiers to Helicopter Beard’s easy money promises in an apparent attempt to reduce uncertainty over any eventual exit strategy. To that end, Beard & Co. (not the Milwaukee brokerage firm) have likely been successful. While their dove-ish leanings driven by the mortal fear of a liquidity trap were already well known to all, it now seems almost certain that the Fed will keep the taps flowing until there is tangible economic recovery significant enough to cause improvement in the labor market. This has very worrying implications for inflation- blame the Congress, the Full Employment Act, and the politicization of economic policy.

James Grant and other similarly sensible folk have long highlighted the absurdity of the modern Federal Reserve and its dangerous focus on attempting to maintain inflation by whatever favored index it chooses to manipulate, which is relevant to only those Americans that require neither heat, electricity, nor food (crackheads?). Any discussion of inflation driven by artificially low Fed rates should arguably include not only commodity prices (which were an important component of the last period of costly inflation), but the prices most sensitive to interest rate fluctuations- those of financial assets.

The fundamental underpinnings of risk assets have long since disconnected from economic reality but are widely intelligible in the context of a market broadly gaming the Fed’s accommodative policy, long liquidity and short dollars. Despite being prematurely declared dead on several occasions, the robust bull run has been surprisingly resilient and broadly-based and seems likely to continue absent a major external shock or an unexpected Fed hike. The recent up-trend in gold, which has traditionally been regarded by more hawkish central bankers (the Volcker Fed zum beispiel) as a market signal of the need to tighten offers a counterpoint to the relatively benign movement in the CPI.

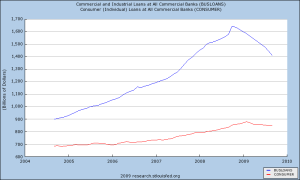

Inflation has remained constrained to financial assets as significant deflationary forces remain in the real economy owing to the slow and painful deleveraging process. This is observable in the falling velocity of money and in the lack of credit growth which have offset the large uptick in M2 and the prolonged period of near-zero interest rates. A revived credit mechanism, which by definition will precede any real economic recovery, has the potential to re-couple the real and financial economies in a dangerous fashion. Until there is credit growth, inflation will be restrained. Until there is credit growth, there won’t be substantial economic recovery, which is likely to be the soonest point at which the Fed withdraws its support. It may then be necessary for the Fed to suddenly reverse its position to halt an inflationary process that will already have moved beyond its control- given their less than stellar record of implementing counter-cyclical policy, I guess this really wouldn’t be that surprising. The worrisome fiscal dynamic complicates the situation, but the Congress will likely only act to check fiscal profligacy until it is faced with a serious crisis- inflation or weak demand for Treasury auctions are both possibilities- that’s a topic for another post.

The delicate situation of the government’s recently purchased banking dependents adds further support to the Fed-overshoot hypothesis (the ol’ ‘Fed tightening bankrupts the marginal borrower’) . Raising rates could inflict serious pain on lenders and would begin to narrow the enormous lending spreads that are allowing banks to gradually patch up their balance sheets. The ‘earn your way out’ exit has long been a policy of Federal bank regs and was last seen on a large scale in the pre-RTC response to the S&L crisis- do whatever you have to to make them nominally solvent, give them explicit government backing and cheap credit, and then tell them to earn their way out (the preferred route then was to plunge headfirst into commercial real estate and HY debt). Unsurprisingly, this isn’t a good idea. It’s akin to inviting the survivors of the substance-abuse orgy you’ve hosted to stay with you until they get back on their feet, with a promise to lend them however much money it takes to repay the crippling gambling debts they owe to your neighborhood loan shark. In the best case, you’ll likely be out the cash you lent them and in the worse you’ll be robbed blind by a bunch of conniving thugs.

Adding these perverse incentives to the Fed’s limited policy flexibility and what amounts to a stated preference for inflation suggests the Fed is headed for a type-1 error of enormous inflationary potential. The seemingly contradictory flattening of near interest rate futures alongside a widening of TIPS breakevens is consistent with the view advanced above of a market in the intermediate stage of a fiscal and monetary policy-induced inflationary spiral, as are the widely divergent inflation forecasts of market observers, for all that’s worth. Until the Fed moves to limit the impact of loose monetary policy, the most likely result is the continuing strength of a dangerously frothy market built on little more than cheap money being used to game federally-inflated asset bubbles. Sound worryingly familiar?

-bleichröder

Type 1 Fed Policy and the Decoupling of Equity Markets

The Federal Reserve’s stated goal of moderating the business and credit cycle while maintaining full employment through enlightened policymaking demands a macroeconomic understanding of such a comprehensive and elegant nature as to rank alongside a quantum theory of gravity. It also largely explains the surprisingly resilient decoupling of risk assets from fundamental reality.

While I hate to add to the heap of market-as-degenerate gutter drunkard analogies tossed around by the media and punditry (especially in my first post), here’s one more for you:

William McChesney Martin lived in an era before date rape drugs were widely available and the old notion that the Fed’s job is to ‘take away the punch bowl at the party’ before things get too crazy seems a bit outdated, particularly given the unprecedented scale of government involvement in capital markets. The events of the past year have generated a policy response more akin to throwing a carte blanche booze and drug bonanza with the hopes that you’ll be able to gradually cut off the raging crowd before anyone gets out of control and your place is burned to the ground. Think something between a Big-10 game day kegger and the party Jonny Depp throws in Blow.

Last week’s FOMC statement added a series of qualifiers to Helicopter Beard’s easy money promises in an apparent attempt to reduce uncertainty over any eventual exit strategy. To that end, Beard & Co. (not the Milwaukee brokerage firm) have likely been successful. While their dove-ish leanings driven by the mortal fear of a liquidity trap were already well known to all, it now seems almost certain that the Fed will keep the taps flowing until there is tangible economic recovery significant enough to cause improvement in the labor market. This has very worrying implications- blame the Full Employment Act and the politicization of economic policy.

James Grant and other similarly sensible folk have long highlighted the absurdity of the modern Federal Reserve and its dangerous focus on attempting to maintain inflation by whatever favored inflation index it chooses to manipulate, which is relevant to only those Americans that require neither heat and electricity or food (inner city rock hoes?). Any discussion of inflation driven by artificially low Fed rates should arguably include not only commodity prices (which were an important component of the last period of costly inflation), but the prices most sensitive to interest rate fluctuations- those of financial assets.

The fundamental underpinnings of risk assets have long since disconnected from economic reality but are widely intelligible in the context of a market broadly gaming the Fed’s accommodative policy, long liquidity and short dollars. Despite being prematurely declared dead on several occasions, the robust bull run has been surprisingly resilient and broadly-based and seems likely to continue absent a major external shock or an unexpected Fed hike. The recent up-trend in gold, which has traditionally been regarded by more hawkish central bankers (the Volcker Fed is a good example) as a market signal of the need to tighten offers a counterpoint to the relatively benign movement in the CPI.

Inflation has remained constrained to financial assets as significant deflationary forces remain in the real economy owing to the slow and painful deleveraging process. This is observable in the falling velocity of money and in the lack of credit growth which have offset the large uptick in M2 and the prolonged period of near-zero interest rates. A revived credit mechanism, which by definition will precede any real economic recovery, has the potential to re-couple the real and financial economies in a dangerous fashion. Until there is credit growth, inflation will be restrained. Until there is credit growth, there won’t be substantial economic recovery, which is likely to be the soonest point at which the Fed withdraws its support. It may then be necessary for the Fed to suddenly reverse its position to halt an inflationary process that will already have moved beyond its control. Attempting to control for the failings of fiscal policy with monetary policy can be a messy exercise, and if the Fed waits too long before tightening it will move from fighting deflation to inflation. Given their less than stellar record of implementing counter-cyclical policy, I guess this really isn’t that surprising.

The delicate situation of the government’s recently purchased banking dependents adds further support to the Fed-overshoot hypothesis. Raising rates could mean serious pain for lenders and would begin to narrow the enormous lending spreads that are allowing banks to gradually patch up their battered balance sheets. The ‘earn your way out’ exit has long been a policy of Federal bank regs and was last seen on a large scale in the pre-RTC response to the S&L crisis- do whatever you have to to make them nominally solvent, give them explicit government backing and cheap credit, and then tell them to earn their way out (the preferred route then was to plunge into commercial real estate and HY debt). Unsurprisingly, this isn’t a good idea. It’s akin to inviting the survivors of the substance-abuse orgy you’ve hosted to stay with you until they get back on their feet, with a promise to lend them however much money it takes to repay the crippling gambling debts they owe to your neighborhood loan shark. In the best case, you’ll likely be out the cash you lent them and in the worse you’ll be robbed blind by a bunch of conniving thugs.

Adding these perverse incentives to the Fed’s limited policy flexibility and what amounts to a stated preference for inflation suggests the Fed is headed for a type-1 error of enormous inflationary potential. In the meantime, market action will remain puzzling.

The seemingly contradictory flattening of near interest rate futures alongside a widening of TIPS breakevens is consistent with the view advanced above of a market in the intermediate stage of a fiscal and monetary policy-induced inflationary spiral.

This transitional character of a market facing retreating deflationary and emerging inflationary forces has likely contributed to the huge discrepancy of inflationary expectations among market observers.

Some recent research has suggested the Hoover administration’s policy failure had less to do with deflationary monetary and fiscal policy and more to do with artificially boosting real wages above the market clearing rate, creating a massive employment gap by attempting to temporarily maintain full employment. Germany’s Kurzarbeit program

Leave a comment